Dr. Syed Ayaz Ahmad Shah:

Highlights:

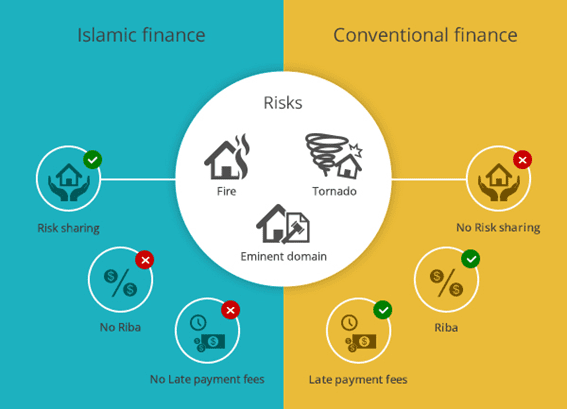

- Islamic finance prohibits interest and promotes ethical, asset-backed, and risk-shared transactions.

- Instruments like Murabaha, Ijara, Musharakah, Istisna, and Sukuk are being actively used in real estate.

- The global Islamic finance industry manages over $3 trillion in assets as of 2024.

- It appeals to both faith-based and ethical investors, promoting financial inclusion and stability.

- Challenges include regulatory barriers, low awareness, and lack of standardization outside Muslim-majority regions.

As the global real estate market becomes increasingly diverse, dynamic, and digitally interconnected, an age-old financial system rooted in religious ethics is gaining renewed attention. Islamic finance, governed by Shariah principles, is rapidly emerging as a viable and attractive framework for real estate investment and development around the world. With its core focus on fairness, transparency, and shared risk, Islamic finance stands in stark contrast to conventional lending models—and in many ways, complements the very nature of real estate, which is inherently tied to tangible assets and long-term commitments.

The fundamentals of Islamic finance may appear unfamiliar to many outside the Muslim world, but they are deeply entrenched in centuries of economic practice, dating back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). The framework prohibits riba (interest), gharar (excessive uncertainty), and investments in haram (forbidden) industries such as gambling, alcohol, and unethical enterprises. Instead, Islamic finance encourages real economic activity, profit-sharing, and ethical conduct.

These foundational values make it especially well-suited for the real estate sector, where long-term partnerships and asset-backed financing are critical. As of 2024, the Islamic finance industry has expanded to manage over $3 trillion in global assets, with a substantial portion allocated to real estate and infrastructure. The expansion is not limited to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) or Southeast Asia—non-Muslim-majority nations like the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Luxembourg are also developing Islamic finance hubs and exploring Shariah-compliant real estate instruments.

One of the primary vehicles in this system is the Murabaha contract, a cost-plus sale mechanism wherein a financial institution purchases a property and resells it to a client at a profit. While it may appear similar to a conventional mortgage, the difference lies in the absence of interest and the actual transfer of asset ownership. Murabaha is especially useful in jurisdictions without Islamic banks, offering devout Muslims a Shariah-compliant way to own homes.

Another popular model is Ijara, or lease-to-own, where the bank retains ownership of a property while leasing it to a client who will eventually become the owner, either through gradual payments or a final balloon payment. This model is particularly effective for commercial real estate or long-term rental arrangements where both parties wish to build equity gradually while maintaining flexibility.

Perhaps the most collaborative of Islamic finance instruments is the Musharakah, especially its Diminishing variant. Here, the client and the bank jointly purchase a property, and the client incrementally buys out the bank’s share over time while paying rent on the bank’s ownership portion. This structure promotes equity, mutual benefit, and fairness—hallmarks of Islamic financial ethics. It also mirrors the real-life gradual transition of ownership that most real estate projects experience.

For new developments, Istisna contracts offer a compelling solution. These are forward-sale agreements where an asset is built to order using funds provided by the financier, and later leased back to the client through Ijara. In this way, Islamic finance accommodates the complex and capital-intensive needs of construction and development projects, including custom housing and commercial real estate.

On a larger scale, Sukuk, often called Islamic bonds, have revolutionized the way large real estate and infrastructure projects are financed. Unlike conventional bonds that are debt instruments, Sukuk represent partial ownership in real assets, with returns generated through rental income or project revenue rather than interest payments. This model not only complies with Shariah law but also introduces a more stable and asset-linked investment mechanism, attracting both institutional and ethical investors globally.

The advantages of Islamic finance in real estate are manifold. First and foremost, it offers ethical alignment with the values of fairness, mutual respect, and social responsibility. These attributes resonate not just with Muslim investors, but also with the growing segment of socially responsible investors (SRI) worldwide.

Furthermore, Islamic finance inherently avoids speculative bubbles by requiring all transactions to be backed by tangible assets. In a market prone to volatility, this asset-linked model offers a buffer against instability. Financial products are designed for long-term engagement, making them suitable for real estate ventures that require extended timelines, phased development, and sustained capital flow.

Additionally, Islamic finance plays a significant role in financial inclusion, especially for communities that avoid conventional banking for religious reasons. This opens up real estate investment and home ownership to a previously underserved population, thereby supporting both community development and market expansion.

Nevertheless, challenges remain. In countries where Islamic finance is not widely practiced, the lack of regulatory infrastructure tailored to Shariah-compliant products often acts as a barrier to adoption. Legal ambiguities and tax treatment issues can complicate matters for developers and investors seeking to enter this space.

Equally significant is the issue of awareness and education. Many stakeholders—whether they are homebuyers, real estate developers, or policy makers—are unfamiliar with Islamic finance’s structures and benefits. This leads to misconceptions or hesitations, which could be addressed through targeted educational initiatives and cross-sector collaboration.

Standardization is another critical concern. Islamic finance is interpreted through various schools of Islamic jurisprudence, and compliance criteria can vary significantly across institutions and countries. This inconsistency often creates confusion for global investors or multinational developers trying to apply Shariah-compliant models uniformly across jurisdictions.

Moreover, the integration of Islamic finance with global capital markets is still evolving. While Sukuk issuance is growing, it still lacks the depth and liquidity of traditional bond markets. Bridging this gap will require continued innovation, robust legal frameworks, and broader investor education.

Despite these hurdles, the future of Islamic finance in real estate appears promising, particularly in light of emerging trends such as the rise of green Sukuk and the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles. These developments align well with Islamic finance’s inherent focus on stewardship, justice, and responsible investing.

The advent of Shariah-compliant fintech platforms is also transforming the landscape, enabling crowdfunding models that democratize access to real estate investment. This innovation not only appeals to the younger, tech-savvy generation but also aligns with the Islamic emphasis on inclusive economic participation.

In a world increasingly seeking ethical alternatives and resilient financial models, Islamic finance offers more than a religious solution—it provides a holistic framework for achieving sustainable, inclusive, and responsible real estate development. As real estate markets globally grapple with inequality, speculation, and housing crises, Islamic finance stands out not only as a financial tool but as a moral compass—guiding investment toward shared prosperity and community well-being.

In the words of many scholars and financial analysts, embracing Islamic finance is not just about accommodating faith—it is about reimagining the purpose and practice of finance itself.

With increasing cross-border collaboration, educational outreach, and regulatory evolution, the real estate sector is well-poised to benefit from the values and structures of Islamic finance. And as more developers, investors, and policymakers recognize its potential, the path toward a more equitable and ethical marketplace becomes not only possible but inevitable.

References

- Iqbal, Z., & Mirakhor, A. (2007). *An Introduction to Islamic Finance: Theory and Practice*. Wiley Finance.

- Usmani, M. T. (2002). *An Introduction to Islamic Finance*. Idaratul Ma’arif.

- El-Gamal, M. A. (2006). *Islamic Finance: Law, Economics, and Practice*. Cambridge University Press.

- Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI). (2021). *Shariah Standards*. Available at: https://aaoifi.com

- International Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB). (2023). *Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report*. Available at: https://www.ifsb.org

- Shafii, Z., Abidin, A. Z., & Salleh, S. (2015). ‘Post-Crisis Real Estate Financing Through Islamic Contracts: A Proposal for Diminishing Musharakah.’ *International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues*, 5(Special Issue), 77–82.

- Ernst & Young (EY). (2020). *Global Islamic Banking Competitiveness Report*. Available at: https://www.ey.com

- Thomson Reuters & ICD. (2018). *Islamic Finance Development Report*. Available via: https://www.refinitiv.com

- Goud, B. (2020). ‘How Islamic Finance Can Support Affordable Housing.’ *Islamic Finance News*. Available at: https://www.islamicfinancenews.com

- Securities Commission Malaysia. (2022). *Sukuk Guidelines & Framework*. Available at: https://www.sc.com.my

For more blogs, visit nyn.press